Last post in this “Keeping Your Favorite Apps Closer” sub-series, I promise, and today’s installment will be short. The last place for keeping your frequently-used apps close at hand (not counting programs that have a part that keeps running in the background and leaves a mini-icon in the Taskbar Notification Area) is the Desktop. And adding icons to the Windows 11 Desktop is pretty much the same as adding icons to the Desktop in previous versions of Windows, most notably Windows 10.

The main thing to remember about adding icons to the Desktop is that, for the most part, you want to create shortcuts to the programs you want, not move the icons or program executables there. The reason I mention this is that the most intuitive way to put an icon on the Desktop is to drag and drop it there. But in this case, that’s exactly what you don’t want to do. That’s because unless you’re familiar with the nuances of Windows’ drag-and-drop behavior, you may not realize that when you drag and drop something from one folder to another on the same drive, Windows moves the item. When you drag and drop from one drive to a different drive, Windows copies the item. Personally, I was never very good at remembering this subtlety, but I learned a long time ago (back when Windows XP was the most popular operating system, I think) that if you drag and drop using the right mouse button instead of the left, then Windows pops up a context menu at the destination, and that menu asks you explicitly what you want Windows to do with whatever you just dragged and dropped.

Windows offers multiple ways to do most things, and copying, moving and creating shortcuts in File Explorer are among them, so it may not surprise you to learn that you don’t have to drag and drop with the right mouse button to accomplish what we’re after today. If you hold down the [Ctrl] key while dragging and dropping with your left mouse button, Windows copies the item. Hold down the [Shift] key while dragging and dropping with your left mouse button, it moves the file. And if you hold down the [Alt] key while doing this, it creates a shortcut at the destination. Intuitive enough for you? Me, neither! That’s why we’ll be dragging and dropping with the right mouse button.

(If you’re one of the few, proud, enlightened left-handed Windows users who learned how to set Windows to reverse your mouse buttons, then you normally click and drag with your right mouse button, and you’ll need to remember to use your left mouse button for this exercise.)

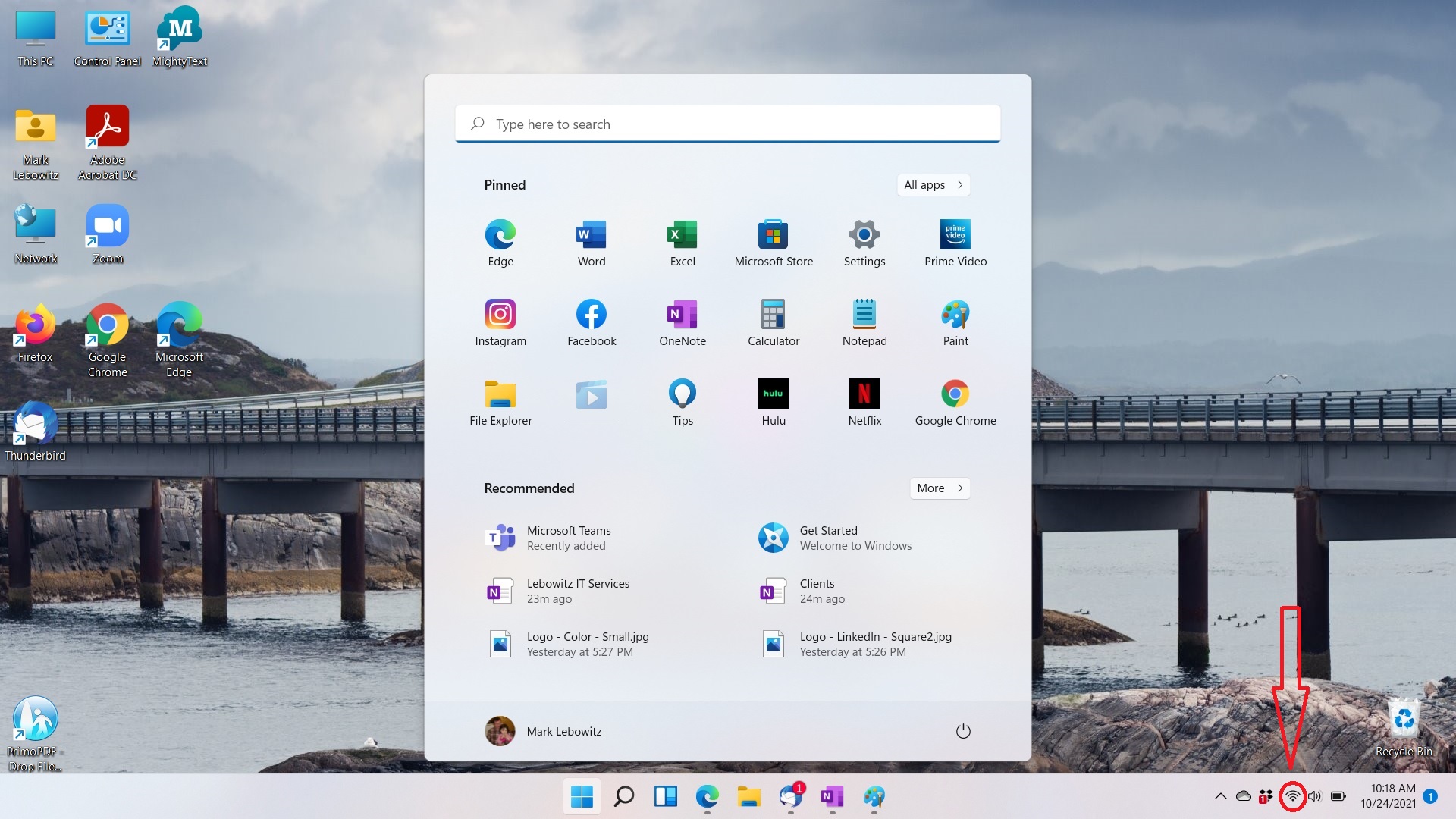

So, let’s get started. The most logical place to look for a program you might want to access from the Desktop is the All apps menu. (Why? Because if you’re sophisticated enough to be running “portable” software from your Downloads or some other folder, then you probably aren’t reading my blog.) So let’s click the Start button and go there:

Next, we click on the “All apps” button (circled), and then go look for something we want on the Desktop. It would be nice to have a shortcut to my printer manual on the Desktop, so let’s right-click on that:

That opens a File Explorer window with the shortcut I want to have on the Desktop. The window may contain multiple program shortcuts; in this case, it contains only one. Now, right-click and hold on the program shortcut you want to copy to the Desktop, drag it out of the window, and drop it on the Desktop as indicated by the arrow:

As shown in the picture, a context menu will appear. Left-click on “Create shortcuts here” (circled). Voila, you now have a Desktop shortcut to the program you want, and you may close the File Explorer window.

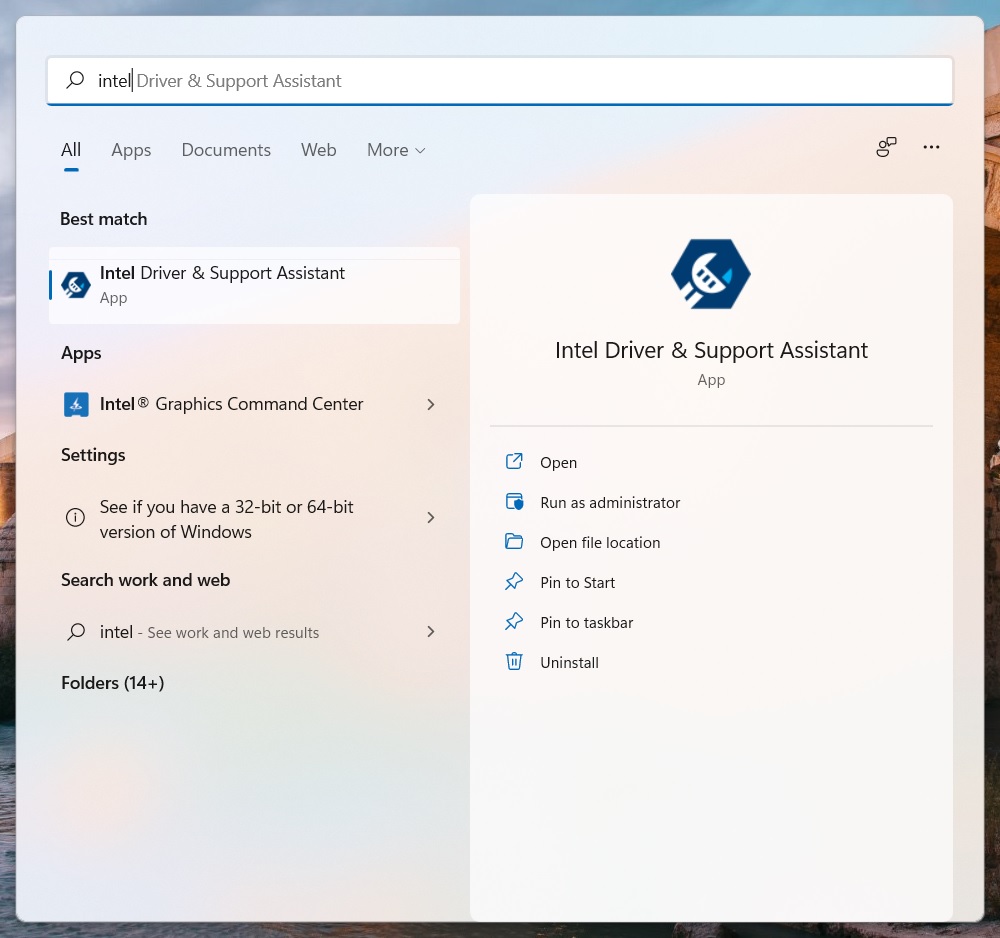

It’s even easier to do this from Start Menu search results, because “Open file location” is in the context menu when you right-click on the item in the search results.

But wait… what if you right-click on an item, but you see an unfamiliar context menu that lacks “Open file location”?

If that happens, it means you’ve clicked on an app that came from the Microsoft Store, what I often refer to as a Windows 11 Sandbox App. (in my case, I right-clicked on “AudioDirector for MSI”.) You can’t create a conventional Desktop shortcut from those because they aren’t run from executable files or shortcuts in File Explorer windows. There is a way to get such apps on the Desktop, but that involves looking up long, arcane strings of gobbledygook, then right-clicking on the Desktop, choosing “New”, then “Shortcut”, and keying them into the Create Shortcut dialog box. That is beyond the scope of this blog entry.

I hope this helps make your programs more convenient to access. Next week, we’ll move on to something completely different.